For amateur climbers, Kilimanjaro can be "evil-spirited mountain"

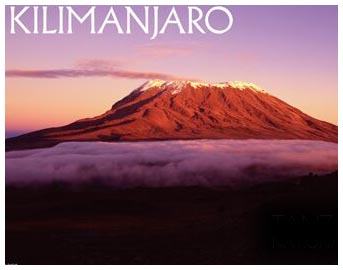

Moshi, Tanzania - Majestically towering above Tanzania's savannah is Mount Kilimanjaro, Africa's highest peak. Several climbing routes lead to the summit through rainforest and lunar-like landscapes. Mountaineering skills are not needed, so about 30,000 tourists annually attempt to reach the top. Not all succeed, though.

Moshi, Tanzania - Majestically towering above Tanzania's savannah is Mount Kilimanjaro, Africa's highest peak. Several climbing routes lead to the summit through rainforest and lunar-like landscapes. Mountaineering skills are not needed, so about 30,000 tourists annually attempt to reach the top. Not all succeed, though.

At the Springlands Hotel, near the town of Moshi at the foot of the mountain, spending a few minutes with the beer-drinking guests on the patio will tell you which ones made it, which did not, and which still have an attempt ahead of them.

Those who succeeded smile and recount their six-day struggle against heat and cold, but mainly against their weaker selves. "It was worth it despite the hard slog," concluded Ian Richardson, a Briton now barely able to walk.

Others tell of blisters and headaches; most of them abandoned the climb. The rest, still untested, listen with a mixture of admiration, anxiety and excitement.

The next morning, excitement quickly turned to self-doubt. "I'm supposed to climb that?" said Emanuel Heitz, a 20-year-old from Basel, Switzerland. He had long prepared for the trek but suddenly had reservations.

Rising 5,895 metres about sea level, Kilimanjaro, affectionately known as "Kili," is not one of the world's highest mountains. But seen from a bus at its base, it looks like two Mt Everests stacked one on top of the other.

The Machame route to the summit, which starts south-west of the mountain and takes six days, is one of the most beautiful. But it is steeper, and therefore more arduous, than the popular Marangu route, which is the only one that offers accommodation in huts as well as soft drinks for sale. Hence it is sometimes called the Coca-Cola route.

The Umbwe route is even more demanding than the Machame route. And the Lemosho route is particularly lovely. It starts in a forest with elephants and buffaloes, so an armed ranger accompanies climbers on the first day.

The initial stage of the Machame route was an hours-long trek over muddy paths in the rainforest. When the climbing group arrived at Machame Camp, 3,000 metres about sea level, only the heavily laden porters - boys from Moshi - were still full of energy. The tourists had felt a bit guilty when the porters shouldered their backpacks along with the tents and food. Now, though, they felt only boundless gratitude.

In the morning, the rising sun illuminated Kibo, Kilimanjaro's highest summit, firing the climbers desire to reach it. Gradually the rainforest gave way to heath and moorland, and the trail became progressively rockier.

The mountain broke the first climbers in the group that night at Shira Camp, 3,800 metres above sea level: An American couple decided to turn back. About a third of all "Kili" climbers give up after a few days. About 80 per cent of the rest reach the summit.

The third and fourth nights were spent at Barranco Camp and Karanga Camp, respectively. The day after that was hard. "Today the name of the game is 'pole, pole,' otherwise, we won't make it," warned Ambrose, our mountain guide. "Pole, pole" means "slowly, slowly" in Swahili. They are words Tanzanians live by, and also the formula for a successful ascent.

The climb to Barafu Camp, 4,600 metres above sea level, is steep and strength-sapping. Malte Zapel and Susanne Alisch, teachers from the German port of Kiel, slowly put one foot in front of the other. They had taken the Lemosho route, which converges at this spot into the Machame route.

"So far, the route has been beautiful but strenuous. And I never thought it could be so cold at the equator," said Zapel, one of the few climbers not too out of breath to speak. All was quiet save the whistling of the wind - and the nearly humiliatingly cheerful "jambo" ("hello") of the light-footed porters going by.

On the evening before the final ascent, Ambrose awakened the group at 11:30 p. m. for hot tea. The main reason for setting out so early was to see the sun go up from Africa's highest point. But there was another, psychological reason for the night climb: to keep the group from getting discouraged by a clear view of the steep slope ahead.

The climbers' feet felt almost leaden. At 3 a. m., the temperature was a nearly intolerable 25 degrees centigrade below zero. More and more climbers gave up or fell behind. All wondered now why they had taken on the challenge. Though the meaning of "Kilimanjaro" in Swahili is not entirely clear, at this point the climbers would have translated it as "evil-spirited mountain."

The dark trail led through jagged ice fields. With the last ounce of their strength, the group finally arrived at Uhuru Peak, the highest point of the volcanic cone called Kibo.

The first people known to have reached the Kibo summit were German geographer Hans Meyer and Austrian mountaineer Ludwig Purtscheller. The year was 1889, when what is now Tanzania was part of the protectorate of German East Africa. Meyer named the peak "Kaiser- Wilhelm-Spitze" (Emperor Wilhelm Peak) after the German emperor.

Zapel and Alisch fell into each other's arms, exhausted. They were among the first to see the sun in Africa on this morning. Below them lay a sea of clouds. It was hard to believe that the savannah - with its elephants, lions and giraffes - was underneath.

The next evening, after having taken their first shower in days, the peak's conquerors were sitting in the Springlands Hotel. They proudly recounted their adventures, while the new arrivals listened rapt and with worried faces. (dpa)