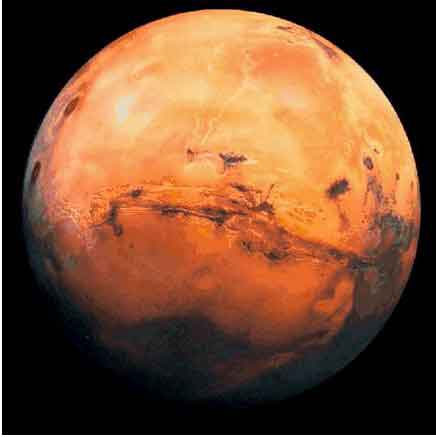

Mars clay “layer cake” adds to evidence of the red planet’s watery past

Washington, August 8: A new study has suggested that a Martian “layer cake” of clay minerals sliced open by an ancient channel adds to evidence of the red planet’s watery past.

Washington, August 8: A new study has suggested that a Martian “layer cake” of clay minerals sliced open by an ancient channel adds to evidence of the red planet’s watery past.

According to a report in National Geographic News, a deposit of four-billion-year-old clays—some of the oldest exposed minerals on the planet—extends over a wide area in the western part of the channel, suggesting that a large body of water once covered the region.

The clays could be key to determining which areas of Mars, if any, were habitable and how long life-sustaining conditions might have lasted.

“We see big, deep clay deposits, so there must have been water for a long time,” said study co-author Janice Bishop of the SETI Institute and NASA Ames Research Center in Mountain View, California. “And we see different types of clays, so there must have been some interesting chemistry going on,” she added.

“Clays really need standing water (to form) and we can see that this is a huge clay deposit,” said Bishop.

Bishop and colleagues pored over images from NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and mapped the distribution of clays known as phyllosilicates in the Mawrth Vallis channel.

An instrument on board the Mars orbiter records the unique wavelengths of light given off by different minerals on the Martian surface.

Using these so-called spectral images, the team identified a layer of clays rich in iron and magnesium exposed in the Mawrth Vallis channel.

Based on the way clay minerals form on Earth, the scientists think the iron- and magnesium-rich layer was most likely created as water altered basalt, a volcanic rock that is common on Mars.

More recent layers above these minerals contain clays high in aluminum.

These may have been formed as water dissolved the iron and magnesium out of the soil or by changes to the chemistry of ancient Martian groundwater, according to researchers.

According to Bishop, other chemical changes in the clays, such as differences in the iron oxidation state in some layers, point to a major event that somehow heated up Martian water billions of years.

“Possibly a volcano erupted, or maybe some kind of impact made the water hot,” she said. “There are a lot of things that could have taken place, and the hard thing is that it happened four billion years ago,” she added. (ANI)