Whale sharks turn Philippine fishermen into activists

Donsol, Philippines - When fish stocks decline, coral reefs die and sea levels rise due to ever accelerating climate change, populations in coastal areas become the first human victims.

Donsol, Philippines - When fish stocks decline, coral reefs die and sea levels rise due to ever accelerating climate change, populations in coastal areas become the first human victims.

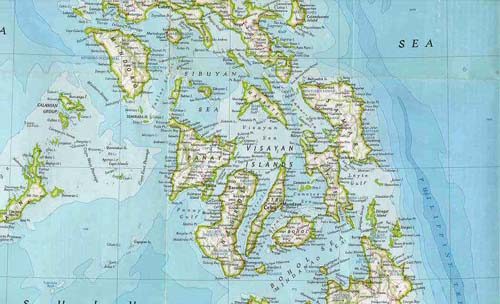

But instead of becoming victims, fishermen in Donsol, some 600 kilometres south-east of the Philippines' capital Manila, have matured into active protectors of their environment.

Between December and May, more than a hundred fishermen in Donsol rarely take their boats to sea in order to haul in a catch.

Instead, they earn a living by acquainting tourists with the largest fish on earth, whale sharks.

The bay of Donsol not only serves as the feeding grounds for the giant fish, but the recent find of a baby whale shark suggests that they also rear their young here.

"We are here to observe [the whale sharks], not to disturb them," Alloy, 36, reminds the tourist group that has gathered on board his boat before they all jump into the water in full snorkeling gear. Outside the shark-watching season, Alloy catches tuna, swordfish and sardines on this boat.

Less than 10 metres from the boat, the group spots its first whale shark, as it approaches slowly and elegantly, almost like in slow-motion.

The group follow the colossus for a while, before it descends deeper and vanishes.

The fisherman on the boat usually spots four, five, sometimes up to eight specimens during a regular three-hour tour, and the tourists are always fascinated by the chance to observe the animals close-up in their natural habitat.

Whale sharks can grow up to 20 metres long and weigh up to 34 tons, the environmental organization World Wildlife Fund for Nature (WWF) says.

It was WWF staff that taught Donsol's fishermen how to interact with whale sharks and tourists to make possible such gentle inter-species encounters.

The fishermen and boat crews, the beachfront restaurants and small hotels are all concerned about the wellbeing of "their" whale sharks, or butanding, as they are called in the local dialect.

It hasn't always been that way.

"Previously, we thought of these giant fish as a nuisance because they tore up our nets," says fisherman Gilbert Guadamor, 37.

But things have changed, and today some of the whale sharks, easily to tell apart by the unique patterns on their backs, have even got nicknames from the locals.

Guadamor has become one of the staunchest advocates of protecting the ocean waters that lap at his front door.

The ecotourism initiative was indeed so successful that it could welcome some 12,000 snorklers this season.

"But we must keep the number of visitors in check, or otherwise they will scare the fish away," cautions Guadamor.

Prior to having been pronounced a protected species by the Philippine government in 1998, whale sharks could be hunted.

Their meat was mostly shipped to Taiwan, where it was a much sought-after delicacy.

With the protection in place, even the smallest whale shark ever discovered, only 38 centimetres long, had to endure only a few hours of terror in March before regaining its freedom.

Two men had offered the fish to the owner of an aquarium near Donsol, but luckily it was rescued and released after WWF staff had received a tip-off.

"It probably was just a few days old," says WWF representative Elson Aca.

The WWF is currently researching the sharks' migration routes, and which ocean current flushes the large amounts of plankton into Donsol bay that attracts the animals.

"It is good to know that they are vegetarian," remarks a female visitor after just learns in the WWF's visitor's center in Donsol that whale sharks have teeth and the mouth is

1.5 meters wide.

"That is not true," replies Aca, briefly shocking the woman. Whale sharks are filter feeders. They suck in water, trap the plankton and expel the water through the gills. They don't use their teeth in feeding.

"They also feed on tiny crabs and shrimps. But don't worry, they would spit out humans as inedible," he smirks.

From Monday to Friday, an international World Ocean Conference in Manado on Indonesia's Sulawesi island is set to discuss the effects of climate change on the world's oceans and its inhabitants.