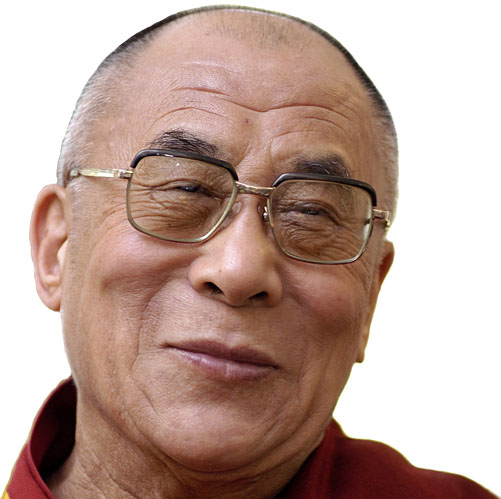

Canadian researchers reveal how they cracked Chinese spy scam on Dalai Lama

Toronto (Canada), Mar. 30: A 34-year-old international relations student and part-time tech geek Meet at Toronto's Munk Centre for International Studies tried everything to track down a piece of malicious software that had infected computers around the world, including those in the offices of Tibetan spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama.

Toronto (Canada), Mar. 30: A 34-year-old international relations student and part-time tech geek Meet at Toronto's Munk Centre for International Studies tried everything to track down a piece of malicious software that had infected computers around the world, including those in the offices of Tibetan spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama.

Finally, he turned to the ultimate hacker's tool: He entered some of the code from those infected computers into Google. Just like that, he found one of the cyber-spy network's control servers, then another, and another. From that Eureka moment came a flood of information, almost all of it suggesting the ring originated in China.

A team of Canadian researchers revealed this weekend a network, dubbed GhostNet, of more than 1,200 infected computers worldwide that includes such "high-value targets" as Indonesia's Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Indian Embassy in Kuwait, as well as a dozen computers in Canada.

The revelation left government bodies around the world scrambling to determine what sensitive files may have been compromised by the cyber-spy network, which even now continues to spread and infect, its authors apparently undaunted by all the extra attention.

The revelation that the vast majority of the attacks appear to originate from China has prompted an angry denial from Beijing, which slammed the report as nonsense.

It is hard to believe that the search for the origins of the massive cyber breach began just a few months ago in a room at the foothills of the Himalayas, with a Canadian researcher watching a 'ghost' steal a file from the Dalai Lama.

Greg Walton showed up in Dharamsala in September of last year to determine whether somebody was trying to spy on the Dalai Lama's computer.

With a background in international relations and computer science, British-born Walton had been advising the Tibetan government on security issues since the late 1990s. The Dalai Lama's Geneva-based adviser had recently asked him to check whether Tibetan government computers had been the subject of an attack.

"We were granted unprecedented access to the private office and to the computer systems," says Walton, who is one of three researchers at the Munk Centre's Citizen Lab - along with Villeneuve and lab head Ron Deibert - who worked on the 10-month investigation in conjunction with the SecDev Group, an Ottawa-based consultancy.

What Walton found was a thoroughly compromised computer system, infected with so-called "malware" that allowed a mysterious outside entity to not only spy on the computer, but also extract data from it. Researchers watched someone, somewhere, extract a copy of a document detailing the negotiating positions of the Dalai Lama's envoy.

"What we were witnessing was an international crime taking place," says Professor Deibert.

Walton recorded the activity and eventually returned to Toronto with some 1.2-gigabytes of raw data - countless lines of often-incomprehensible code - for Villeneuve to sift through.

The researchers at the Citizen Lab weren't new to this kind of thing. Last year, they revealed the logging of millions of text messages sent by users of a Chinese Skype service. Mr. Villeneuve had learned some tricks during that endeavour, such as searching for improperly configured servers and sifting through their directories for useful files.

He tried the same tricks this time, but nothing worked. The researchers knew there was a backbone behind the malicious software on the Dalai Lama's office computers, but they couldn't pinpoint it.

Then one day, a couple of weeks ago, Villeneuve came across a line of code that appeared to begin with a numbers that signified a date.

In an interview on Sunday, he was momentarily reluctant to disclose the seemingly elite hacker's tool he unleashed on that piece of code in order to get it to spill its secrets.

Finally, he said: "I put it in Google, man."

The obvious paid off. Soon, Villeneuve was led to a U. S.-based server that turned out to be one of the so-called "control" servers behind the malicious code.

Whoever Villeneuve was following turned out to be very systematic in his approach, and the researcher found that changing a single number or letter in a piece of code led him to another control server.

Soon, the investigators found four control servers, each containing a list of all infected computers that have reported to the server, as well as code to issue and monitor commands to the infected computers.

If the 1,295 infected computers in 103 different countries were the limbs, the four servers were the spine, and three of those servers were located in China.

Professor Deibert is cautious not to allege that the Chinese government is behind the cyber spy network, saying he simply does not have hard evidence to support that conclusion. What the researchers do have is circumstantial evidence.

"The evidence that we have shows that the majority of the control servers were located in China. The interface to controlling the infected hosts on these servers in China was in Chinese. And the remote Trojan favoured by the attackers is a Trojan coded by Chinese hackers," says Villeneuve.

One of the four servers, located in Hainan Island, also traced back to a Chinese government server.

Chinese officials in Canada could not be reached for comment on Sunday, but Beijing has reportedly denied any involvement in the cyber spy ring, slamming the investigation's findings. (ANI)