NYT describes Benazir's tome as a work of `enormous intelligence'

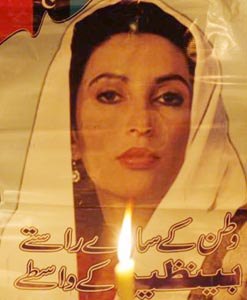

New York, Apr. 7:  Former Pakistan Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto's posthumously published book has been described by the New York Times as a work of "enormous intelligence, courage and clarity", containing the best-written and most persuasive modern interpretation of Islam.

Former Pakistan Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto's posthumously published book has been described by the New York Times as a work of "enormous intelligence, courage and clarity", containing the best-written and most persuasive modern interpretation of Islam.

Reviewing Benazir's book -- Reconciliation: Islam, Democracy and the West -- noted journalist Fareed Zakaria says in the Sunday issue of the New York Times that Bhutto finally managed to close "the gap between ambition and action that haunted (her) for most of her public life."

"Part of what makes it compelling, of course, is the identity of its author. People have often asked when respected Muslim leaders would denounce Islamic extremism and articulate a forward-looking and tolerant view of their religion. Well, Bhutto has done it in full measure," he writes.

"And as the most popular political figure in the world of Islam -- for three decades she led the largest political party in the second largest Muslim country -- she had much greater standing than the collection of reactionary mullahs, second-rate academics and un-elected monarchs who opine on these topics routinely, and are accorded far too much attention in the West. In fact, Washington should arrange to have the portions of the book about Islam republished as a separate volume and translated into several languages. It would do more to win the battle of ideas within Islam than anything an American president could ever say." he adds

Zakaria says that he is particularly impressed with the book's second section, which is about Pakistan and the author. He says that he finds some of it "fascinating" where Benazir describes arriving in Pakistan on October 18, 2007, to tumultuous crowds and then being hit by a bomb blast, the first terrorist attack on her.

"But beyond that, the sections on Pakistan are a mixture of potted history and justifications of her reign and that of her father. There is little introspection and much spin. For example, she implies that she was always opposed to the during her term in office and points out that it took over Kabul as her government was about to be dismissed. But the final takeover, in 1996, came after several years of battle during which Pakistan supported the movement -- under Bhutto's second prime ministership. It is quite possible that she was not in charge of these matters -- the military ran most of the foreign and defence policy during her years -- but she chooses not to admit that either," he says.

Zakaria finds these pages "neither fresh nor frank" and in their lack of candour, he likens them to the memoirs of most politicians.

However, according to the Daily Times, the larger part of the book he finds "stirring and important". He credits Bhutto with taking on issues that most Muslim leaders have preferred to ignore or avoid, such as the sectarian war within Islam.

He notes that she addresses the most backward-seeming traditions in the Muslim world with a knowledge of both theology and history.

She (Bhutto) points out, for instance, that in many Muslim countries it is assumed that the holy Quran requires that women be wrapped head-to-toe in chadors, when that is not the holy injunction, which calls for modesty in dress both for men and women.

He calls her reading of the holy Quran "clever and progressive", which achieves an equality between the sexes without denying the divinity of the text. It is a far more effective way to win over a religious community than to denounce the religion as sexist or backward, he adds.

Zakaria also commends Bhutto for asking Muslim societies to learn to tolerate differences in faith. She links the need for Sunni-Shia harmony with the broader need for respect of other religions.

He notes that she does not accept some of the conventional wisdom about the roots of Islamic terrorism. She discusses the cause and acknowledges its importance but does not claim that it is the source of all Muslim ill will towards the West. She is unsparing in her description of Wahhabi Islam and its home, Saudi Arabia.

Zakaria also finds it striking that Bhutto was willing to write things that would surely have caused her difficulty had she become prime minister. She also dismisses the clash of civilisations theory as false. Zakaria finds her discussion of Pakistan "almost obsessive" in its insistence that United States policy has been responsible for propping up dictatorship and undermining democracy there, though there is "certainly some truth to these claims."

According to Zakaria, if Muslims must accept that they are the authors of their own fate and stop blaming outsiders, is it not fair to ask that of Pakistan's leaders, military and civilian?

He concludes: "The new democratic government in Pakistan might endure and will then have to tackle its country's terrorism problem. One can only hope, for the sake of P akistan, Islam and the world at large, that it succeeds, and that Benazir Bhutto will be vindicated in death in a way she was not in life." (ANI)